Xiomara Castro Delegates to Son, Skips Open Procurement

Key Findings

Honduran President Xiomara Castro has revived the century-old interoceanic train project. The publicly stated aim is to boost Honduras’s economy, but there has been controversy due to concerns about corruption and a lack of transparency. Critics, including former Vice President Salvador Nasralla, have sounded the alarm over the appointment of Castro’s son to lead the project and the decision to bypass standard procurement procedures. This has fueled suspicions of ulterior motives.

The project does promise significant economic benefits, including transforming Honduras into an international logistics hub and reducing traffic through the Panama Canal. These benefits, however, hinge on efficient and complete implementation. Civil society and the media can play a crucial role in overseeing the project by exposing irregularities and noting the challenges posed by the prevailing secrecy.

The project implies feasibility partnerships with international players from South Korea, Spain, the United States, and Japan. However, the incumbent government is also finalizing Chinese funding, potentially opening the door to unfavorable agreements and undesirable geopolitical implications.

Honduran President Xiomara Castro has revived a project originally proposed in the 19th century, as a purported catalyst for economic development in Honduras. The ambitious plan, which is projected to span 20 years and cost an estimated US$20 billion, envisions an interoceanic train connecting the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans.

However, this dream, which dates back almost two centuries, has become a source of renewed controversy. Opposition politicians and analysts are raising red flags about corruption and questioning the true motives behind the latest iteration of the project. These include the appointment of Castro’s son as the project leader, concealed project information, and the provision to bypass standard procurement procedures.

This investigation delves into the status and future prospects of the “Great National interoceanic Railroad Project,” with a focus on the processes that have raised concerns about potential corruption. To shed light on these issues, the Impunity Observer conducted interviews with:

Salvador Nasralla, former vice president and currently a primary presidential candidate for the Liberal Party;

businessman Eduardo Facusse, former president of the Cortés Chamber of Commerce and Industry;

and the leadership of Expediente Público (EP), an investigative magazine in Central America. We will keep the names confidential due to fears of retaliation from the region’s autocratic regimes.

Connecting Oceans through Railways

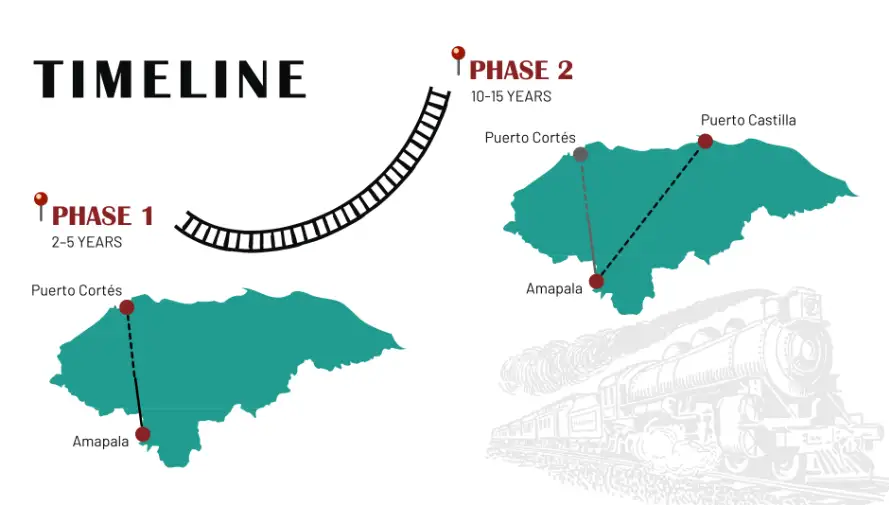

In the first phase of the interoceanic train, the Honduran government plans to renovate the railway lines connecting Puerto Cortés, a key Atlantic Ocean port, with San Pedro Sula, the industrial heart of the country. The plan includes constructing 120 kilometers of new railway line that will extend inland to a dry port in La Barca, in the Cortés department.

From La Barca, an existing highway leads to the Pacific coast, though it requires maintenance. The project will also build 80 kilometers of new railway lines to connect the highway to Amapala, where a new port is under development. Amapala, an island in the Gulf of Fonseca, shares its waters with Honduras, El Salvador, and Nicaragua. This initial phase is slated to take two to five years.

The second phase aims to construct 600 kilometers of railway between Amapala and Puerto Castilla on the Atlantic coast, just east of Puerto Cortés. These two planned maritime points offer strategic advantages with their deep waters, which can accommodate ships up to 300,000 tons. Building this new route will take 10–15 years.

The Honduran government has already initiated feasibility studies, working with international partners, including from China, Japan, South Korea, Spain, the United States. The interoceanic train requires national public-private partnerships to handle 51 percent of the construction, with the remainder open to foreign investment. Fredis Cerrato, the country’s development secretary, revealed to Bloomberg: “China is interested in the projects and requests to prioritize Chinese private entrepreneurs who are willing to participate with costs and the possibility of investment.”

Key industries in Honduras strongly support the project, with the hope that it will significantly boost trade and strengthen the national economy. Mario Canahuati, president of the Honduras Manufacturers Association, optimistically told La Prensa that this project ranks among the most important for the country. He believes “it will transform Honduras into the logistics hub of the world.”

Similarly, the Castro administration has explained the interoceanic railway will reduce traffic at the Panama Canal. Around 6 percent of global trade’s goods traverse the Canal, and the passage of boats gets backlogged when the sea level dwindles due to weather conditions. In July 2023, the Panama Canal Authority reduced the traffic of boats by 20 percent, due to the El Niño phenomenon. From the usual 38 boats that used to cross daily through the Canal, 31 were crossing by the end of last year.

Regarding citizen approval, the EP leadership told the Impunity Observer that the lack of transparency surrounding the project portends to negatively impact its public perception: “While some sectors see it as an opportunity for economic development and job creation, there is significant concern about the lack of transparency and secrecy surrounding the initiative. This absence of detailed and accessible information has fostered distrust among the public.”

Corruption Concerns

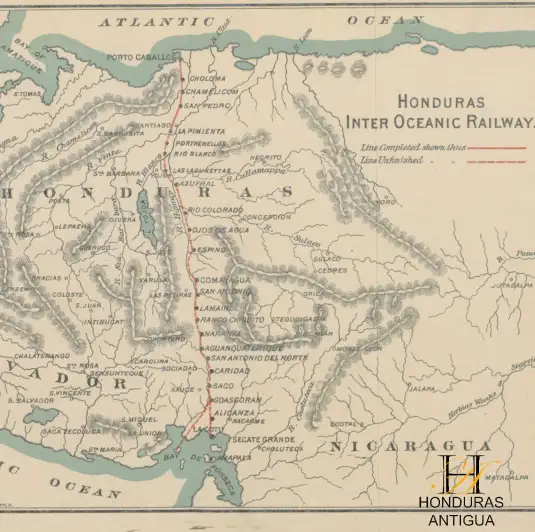

The idea of an interoceanic train in Honduras dates back to 1850, when President José Trinidad Cabañas first proposed a railway connecting the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans. England and France initially invested in the ambitious project. However, after 25 years, the European nations sought accountability from Honduras in French courts.

The invested funds had vanished, while the project was far from over, with only 100 kilometers of railway operational. Despite demands for an investigation, the case stalled, and no further action was taken. Nasralla told the Impunity Observer that “Honduras took around 100 years to pay that debt to England.”

Over the years, various administrations have tried to revive the project, maintaining existing railways, building new lines, and purchasing train engines. By the end of the 20th century, all train operations had ceased in Honduras, although some tracks remain intact but idle.

In 2016, the PanAm Post reported the government’s renewed plans to launch the interoceanic railroad project. At that time, the estimated cost was $10 billion. In contrast, authorities now estimate the project could cost as much as $20 billion.

Presidential candidate Nasralla attributes this cost discrepancy to bribery, alleging the previous and incumbent governments have imposed hidden fees for project approvals. Nasralla warns: “If corrupt politicians remain in power, the final cost could even skyrocket to $50 billion by the time the project is completed.”

In the same vein, the EP leadership asserts: “Businesses and investors tied to the construction and operation of the interoceanic railway have a direct economic interest in the project’s implementation and, therefore, could exert significant influence on the political and administrative decisions. The lack of transparency in the process could allow private interests to prevail over the common good.”

However, the project remains in an exploratory stage, and businessmen await clear structure and planning to kickstart construction. According to former Chamber President Facusse, “the private sector would be very interested in such a project, but it continues to be an idea that needs to be definitively grounded. There is plenty of uncertainty surrounding the project.”

To advance the project, Castro established the National Commission of the Interoceanic Railroad (CONFI) through Executive Decree PCM 08-2024 on February 28, 2024. CONFI will oversee the “planning, formulation, organization, and execution of the ‘Great National Interoceanic Railroad Project.’”

Castro appointed her son, Hector Zelaya, as head of CONFI. Nasralla expresses his doubts: “One cannot assign a project of such magnitude to an inexperienced person. The interoceanic railroad should be overseen by someone knowledgeable about public works, particularly engineering.” According to his LinkedIn profile, Zelaya has experience in executive management, business strategies, and political campaigns.

The decree also grants Zelaya the authority to sign contracts with suppliers for the railroad’s construction using direct contracting, bypassing the usual procurement procedures. This decision has raised eyebrows, since there is no emergency situation justifying the use of the fast-tracked process. Adding to concerns, on March 8, the Castro administration concealed all information related to international negotiations for state strategies, including that of the interoceanic train.

Political analyst Luis León told local media outlet Criterio that while the project could greatly benefit Honduras, its success hinges on strict adherence to legal frameworks: “Ensuring this project’s economic viability and profitability is crucial, but bypassing established procurement laws with direct purchases is undeniably illegal. The State Procurement and Contracting Law clearly outlines the proper procedures.”

The combination of direct purchasing and secrecy has alarmed political analysts, who cite past abuses during the COVID-19 spread as a cautionary tale. During that period, delays plagued the delivery of mobile hospitals purchased from Turkey. Investigations revealed that the Strategic Investment Office of Honduras (Invest H) selected an unqualified intermediary, bypassing required certifications and experience. Additionally, Invest H made a 100 percent advance payment without securing any guarantees of compliance.

Honduras faces challenges reminiscent of the mid-19th century when the train project first began. The country may once again need to resort to foreign debt to fund the construction. Also, the project’s continuity depends on the interests of future administrations, along with avoiding cost overruns and delays. In the last three years, Transparency International has graded Honduras 23 out of 100 points in its Corruption Perception Index.

For the EP leadership, “the civil society and the media can play a crucial role in overseeing the interoceanic train project through active monitoring, demanding transparency, and exposing potential irregularities. However, their capacity for oversight is limited by the secrecy surrounding the project, making it essential to strengthen platforms for information access and press freedom.” If officials’ intentions were truly aligned with economic growth for Hondurans, they would enable anticorruption mechanisms. The EP leadership proposes some of them: “creating an independent oversight commission with civil society participation, conducting regular and mandatory audits by international entities, and requiring all contracts and expenditures to go through public and transparent bidding processes. In addition, Congress could strengthen anticorruption laws and ensure those responsible are held accountable in a meaningful way.”

For Facusse, corruption is a systemic issue that is present in every administration. However, he believes “the Castro administration has been more efficient than the previous government in fiscal management, since it has not resorted to further debt. However, the administration has not contributed to but rather negatively affected the nation’s economic sector.”

Foreign Alliances Could Define the Project’s Future

Despite the economic significance of the interoceanic train, political will has hindered its construction. So, what makes it different this time, with less than two years remaining for the current administration?

The Castro administration has admitted that only studies can be conducted during the remainder of this presidential term. In April of this year, Octavio Pineda, the secretary of infrastructure and transport, told the media: “We need to talk about realities, and the reality is that we only have time to do designs, pre-feasibility studies, and, if everything goes well, then feasibility studies.”

According to Nasralla, one of the leading opposition candidates with a strong chance of winning the presidential election, the project is crucial for boosting trade and jobs in the country: “I am one of the first to support the interoceanic train because I know the history of its construction.”

Nevertheless, Nasralla has doubts about the project’s foundation if the Castro regime secures funding to start it: “I hope they don’t begin construction because, right now, it’s a flawed project. For example, Castro is seeking support from China, when the most logical partner, due to its geopolitical location and our shared history, is the United States.”

Facusse also warns the Castro administration has partnered with antidemocratic left regimes such as Venezuela and Cuba. This has negatively impacted “the business sector’s general perception, since it dwindles its expectations to promote free markets in Honduras.”

Latin America has increasingly become a destination for Chinese state funds, often in the form of burdensome agreements that have left countries indebted and, in some cases, with incomplete public works. Most of these agreements are rooted in antidemocratic foreign policies and include confidentiality clauses.

Moreover, the EP leadership notes: “So far, no detailed information has been publicly disclosed about contingency plans in case the interoceanic train project exceeds its budget or encounters significant delays. This absence of transparent and public planning is concerning, as the lack of preparation could exacerbate financial and operational impacts in the event of unforeseen issues.”

Honduras stands at a crossroads with the revival of the interoceanic train project. While the potential for economic growth and development is immense, so too are the risks of corruption, mismanagement, and foreign debt dependency.

The road ahead requires careful navigation, with strong oversight, transparent governance, and a commitment to the public interest. Without these safeguards, the project could become another chapter in the long history of corruption and unfulfilled promises in Honduras.

The opinion of this article is foreign to Noticiero El Vigilante