Nearshoring Fits Anybody-but-China Strategy

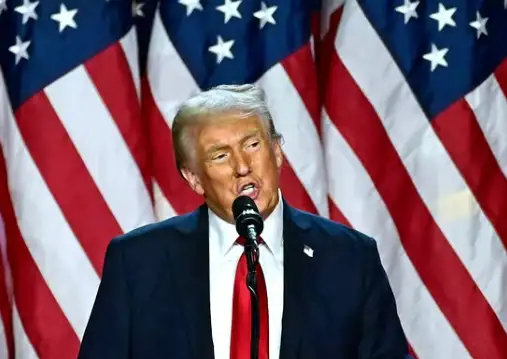

President Donald Trump’s picks for the State Department (DOS) signal a hawkish anti-China pivot and a greater focus on the Western Hemisphere in US diplomacy.

Marco Rubio is well versed in Latin American affairs and a China hawk. The designation of Jacob Helberg, also a China hawk, as the top economic policy official at DOS also foretells the approach to economic statecraft the DOS will pursue: ABC (anybody but China). Mauricio Claver-Carone’s slot as special envoy for Latin America also suggests that Latin America will play a greater role in US geopolitical strategy in the coming years.

Latin America will be key to the DOS’s ABC framework. The first Trump administration promoted a nearshoring strategy to reduce US dependence on Chinese industry. His return is set to rekindle the effort to reindustrialize the Americas.

Nearshoring refers to relocating supply chains and manufacturing operations to countries closer to the United States. One of its main goals is to reduce reliance on China and distant markets by encouraging companies to shift production to Latin American countries like Mexico and Guatemala.

The 2018 United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA), which replaced the 1992 NAFTA deal, facilitated this strategy. The USMCA added provisions to strengthen manufacturing and integrate supply chains in the region. By improving trade relationships within the region, economic activity between the United States and neighboring countries will deepen. This is particularly important, given global supply-chain disruptions and growing Chinese economic influence in Latin America.

Over time, the economies of Central and South America stand to gain from the shift of production from Asia. Countries like Mexico and Guatemala, in particular, are well positioned to benefit from this transition due to their proximity, access to US seaports, competitive labor costs, and established trade agreements like CAFTA-DR—signed in 2004. As companies seek alternatives to Chinese manufacturing, Latin America can emerge as a favorable destination for investment.

The shift to regional industrialization could also reduce the long-run incentive for illegal immigration to the United States by fostering economic development. By providing a plan for creating job opportunities and stimulating local industrialization, nearshoring addresses a root cause of illegal immigration: the lack of economic dynamism and job creation in the region.

The premature deindustrialization of Latin America is one of the main reasons for the lack of economic dynamism and job creation. World Bank data show that, in the 1966–1980 period, Latin American GDP grew at a 6 percent average annual rate, and its industrial and manufacturing sectors even higher than that. In the years between 2009 and 2022, average GDP growth has been less than 2 percent, and less than 1 percent for industry and manufacturing.

Similarly, Mexican GDP grew at a 6.5 percent clip from 1966 to 1980, while its industry and manufacturing grew at similar or higher rates. In the 2009–2022 period, Mexican GDP grew at a 1.5 percent rate, while its industry growth rate was a paltry 0.3 percent. In the case of Guatemala, its GDP grew at a 5.7 percent rate in the 1966–1980 period, while industry and manufacturing grew at approximately 8 percent and 6.93 percent, respectively. Again, we see a drop-off in the 2009–2022 period, where Guatemala’s GDP grew at a 3.3 percent rate, while industry and manufacturing grew at rates hovering around 3 percent.

By contrast, China’s GDP and industry both grew at a 7 percent rate in the 2009–2022 period. Similarly, Bangladesh produced 6.3 percent GDP growth and roughly 9 percent on average for both industry and manufacturing.

A nearshoring boost could propel higher rates of growth in industry, manufacturing, and overall GDP for regional allies, producing well-paying jobs in the formal economy and blunting the incentives for illegal immigration. The problem is real. According to Statista, the illegal-immigrant population in the United States exploded by 230 percent between 1990 and 2010, and has remained exceptionally high ever since.

Nearshoring is a direct response to the vulnerabilities exposed by geopolitical threats such as the ascent of China in Latin America. Other global events, like the COVID-19 pandemic, which highlighted the risks of over-reliance on distant supply chains.

Shifting the industrial supply chain closer to the United States would help ensure that critical goods can be produced within the region, avoiding the potential bottlenecks of relying on far-off overseas production. Further, nearshoring would stem the growing economic power of China, providing benefits to allies in the region on a win-win basis and blunting the incentives for illegal immigration.

Several challenges remain. Latin American countries face significant infrastructure gaps, regulatory hurdles, and the need for workforce development. US businesses require incentives to commit to long-term investments in the region. This is important as FDI from the United States has been on a downward trend in the critical Northern Triangle country of Guatemala. FDI from the United States into Guatemala dropped off 37 percent in the 2019–2023 period, compared to the prior five-year term. US FDI used to represent 27 percent of Guatemalan FDI but now averages only 15 percent. That is a paltry figure considering the importance of Guatemala to the United States’ global and regional geopolitical strategy. Guatemala is the largest country in the world, both in terms of population and GDP, that still diplomatically recognizes Taiwan.

A focus on bringing nearshoring to Central America, and Guatemala in particular, would be a strategic win for the incoming Trump administration. This would align economic and security interests while mitigating global supply chain vulnerabilities and illegal immigration. For the United States’ regional allies, nearshoring could open new avenues for growth, employment, and development.

The opinion of this article is foreign to Noticiero El Vigilante